Thrill Me

Website Review

Andrea Braun – thevitalvoice.com, August 11, 2011

Even as inured as much of society has become to violence, every once in a while, something comes along that horrifies us. Such was the case with the press-dubbed “thrill killers,” Nathan Leopold, 18, and Richard Loeb, 19, whose crime, though committed in 1924, still fascinates us today.

They were possessed of genius IQ’s, both graduated college at 15, and were influenced by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the “superman” (Übermensch), which Loeb (in the play; Leopold in real life) interpreted to mean that superior beings aren’t bound to the same rules as the rest of humanity. Or at least that’s the reading Thrill Me (book, music and lyrics by Stephen Dolginoff) provides.

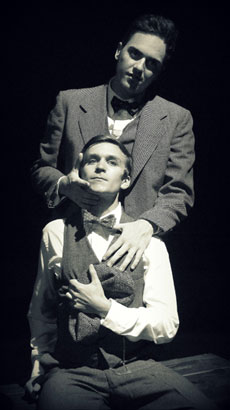

The case is simple, but its motives are not. Most accounts agree that Loeb was the dominant partner and Leopold the follower in this crime. Dolginoff takes the position that Leopold (James Bleeker) was in sexual thrall to Loeb (Blake Berry Davy, who bears a remarkable resemblance to the real guy) and would do anything to please him. They engaged in petty theft and arson, but the “thrill” was gone for Loeb when he suggested committing the “perfect murder.” The idea was to snatch a random child, kill him with a crowbar, disfigure his face and body with acid to render him unidentifiable; then, ice the cake with a ransom note that would allow them to pocket a tidy little profit from the distraught parents. It’s important to note that the Leopold and Loeb families were rich Chicagoans, so getting the money was just part of the thrill.

Loeb has gotten Leopold to sign a contract in blood which effectively says that he’ll do anything Loeb wants him to do in exchange for sexual favors. When Leopold balks at cold-blooded murder, Loeb cites the contract. In a bit of foreshadowing, Leopold jokes about the quirks of Loeb’s stolen typewriter, which later cause the police to trace the ransom note to his machine.

In real life and in the play, the crime could hardly have been less “perfect”: Leopold dropped his glasses near where they hid the body of victim, Bobby Franks, age 14, after having considered killing Loeb’s own brother, John, of whom Loeb is jealous. Thrill Me takes dramatic license with the victim’s identity making him a stranger and depicting Loeb’s playground seduction of him. This particular bit of distortion bothers me because Bobby’s relation to Loeb is a game changer in terms of perception. The victim wasn’t “random,” and he knew his “kidnapper.” Does this make Loeb more or less of a monster? To me, it’s an important fact of the case and could easily not have been changed for the play. Other alterations to the facts as we know them, and there are many, are less significant to the big picture.

The Leopold and Loeb case has been tightly woven into popular culture through novels, films, most notably Meyer Levin’s Compulsion!, later made into a movie in which the names are changed, but the events are mostly accurate, right down to Clarence Darrow’s representation of the men at their trial. Darrow was a noted opponent of capital punishment, and his defense was canny: Instead of trying to make an insanity plea work, Darrow had the accused plead guilty, thereby avoiding a jury trial. He then prevailed upon the judge to consider Leopold and Loeb victims of their own genes and childhood environments—“broken machines” in a Darwinian sense—and minors at that (21 was the age of majority at that time for all purposes, though younger criminals had been executed). Darrow’s strategy worked, and the sentence for murder and kidnapping was “life and 99 years,” which, incidentally, is the title of one of the better songs in the show.

The play opens at Nathan Leopold’s fifth parole hearing in 1958 and is told in flashback. He has now served 34 years, and he is examined by offstage voices (Tj Nicol and Brian Beracha). The story switches back and forth between the hearing where Leopold introduces the events, and 1924 when they are played out. The music and dialogue are interwoven to advance the story. Both Bleecker and Davy are fine singers, and the drama of the piece is aided immeasurably by pianist Henry Palkes whose piano is discreetly placed in the back, upstage right. I found the accompaniment to be the most effective part of the musical landscape of the show. The overture is ominous and sets the mood, and Palkes maintains and unifies the play thematically thoughout .

The acting is impeccable and the direction by Brooke Edwards is sure. The actor’s body language and Edwards’ use of the (small) space lends an operatic feel. Will James Stacy’s simple set (the only color being symbolic spashes of red on the walls and floor) and John Blunk’s dramatic lights both work well. The costumes by Cynthia Lohrmann (right down to spectator wingtips for the dandy Loeb) and Beracha’s sound design are evocative. This production of Thrill Me was born as a student production at Western Illinois University where the two actors are pursuing B.F.A. degrees and Edwards is working on an M.F.A. in directing. As such, it is an excellent effort by all concerned, and by any standards, it’s good, but the play itself is an oversimplified, mediocre telling of a sensational story.